“Change is inevitable. Growth is optional.”

John C. Maxwell

In this article, we delve into common strategy mishaps that occur during implementation – the moment the envisioned grand plan hits the road… meeting the often messy reality of people, teams, culture and processes within organisations causing it to shift and chart its way into unintended territory. We also explore remedies taken from change management theory addressing these situations.

Vastly prevalent among organisations today is the drive to be continually relevant within their customers’ attention sphere; understanding what they regard as important: value for money, attention to detail, corporate values, social and environmental responsibility and swift, positive interaction experience are prime examples. And certainly the expectation for executive management is to look forward both outwards and within itself into what trends, technology and challenges are likely to present themselves to the organisation as it plans its future strategy to adapt, secure and grow its position.

However, as much as the planning stage tries to anticipate the hurdles it will likely face and put contingencies, there is always the risk of cumulative factors slowing down or thwarting any change initiative especially with risk averse corporate cultures. In such scenarios, the operational status quo can seem insurmountable to change without drastic measures designed to instil both loyalty and fear depending on which side of the change you sit on!

It is in this context that I highlight 3 of the culprit factors lurking in the shadows whenever the word ‘change’ gets to meet its match in the operations world:

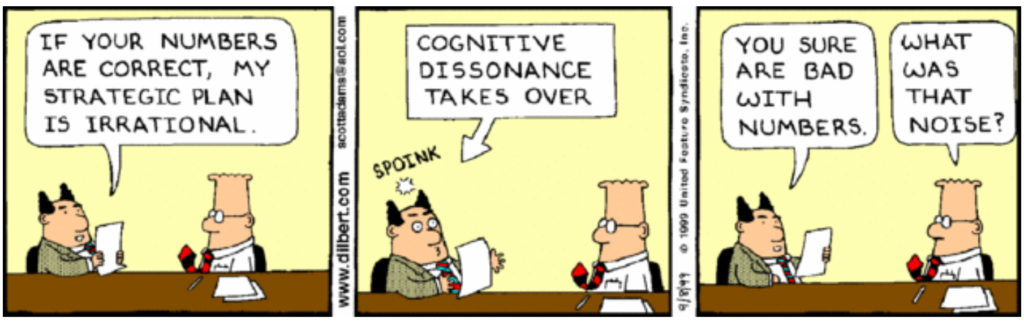

Strategic dissonance

In January this year, Harvard Business Review published an articled titled “A Simple Question to Help Your Team Define Success” which I strongly recommend to any executive embarking on strategic change. The crux of it was about how crucial it is for the executive team to agree on what success feels like in tangible, non-financial terms. Why you ask? It matters to your team to know what winning as a team would look like, and to be able to support each other as cross functional units within the organisation to achieve the bigger goal rather than compete in silos to attain individual accolades instead.

There are multiple ways to realise a strategy; and the reality of paradigm framing when superimposed onto everyday decisions differs from one perspective to the next, so it comes as no surprise to learn that more often than not, the majority of teams within the organisation are not on the same page when it comes to the definition of success and what it means for them to feel successful within the greater collective. This is the start of where a cohesive strategy needs to be broken down to its essence for each team, keeping in mind the alliances and competitive tension existing over budgets, resources and decision making.

Addressing strategic dissonance

Ask the same success question to each leader and gather their responses as to what goals they think need to be set for their future 5 years individually. This way, their interpretation of success and what it means gets comprehensively answered by all along with their interpretations of the goal, methods to achieve it and the reasons to do so in a certain way. It is through analysing what matters to each function within the organisation can the organisation BEGIN to understand its present reality first collectively before agreeing on the right interpretation and hence approach to change in line with a concrete analysis of all considerations taken into account prior to executive consensus over the right strategy put forward.

Under-estimating change anxiety

It is easy to overlook that current work routines and the way teams are assembled are largely driven by employees: their sense of identity, safety, status, values and desires in having control over their work environment. That includes their sense of familiarity, achievement and belonging. So, when change is devised the cautious tale of not taking too much on too quickly is so visceral, real and true.

The sense of loss when it comes to organisational change initiatives is real and it then risks culture clash and resistance reigning supreme among employees who stand, or perceive, to lose owing to moving from one mode where their performance and own teams’ high esteem was anchored to their well-trodden way of doing things, to one where they have to learn and experiment with new technology or processes with the playing field levelled somewhat in certain regards whether the employee is an esteemed senior or a fresh graduate.

Addressing change anxiety

In any change communication messaging, it is equally critical to emphasise what is going to remain unchanged as much as what is slated to change. This creates an anchoring point for employees to feel secured by the familiar along a calculated move towards the novel. Carefully selected champions of change in each team will help walk their team members through the bridge of change: which means detracting from any perceived ‘pain points’ and instead moving the focus on the way forward for possibilities to make work seamless, enriching and forming a meaningful fresh norm that gels better for the organisation; aligning new team goals with the collective goals.

Feedback from change experimentation in itself demands agility to think and react, which brings us to the next point.

Ignoring feedback loops, missing stakeholders

What to do once the execution encounters a hitch: be it snags or a critical flaw? Do we have the corrective action in place to make sure nothing goes a miss from issue diagnosis to refining implementation? And are you including all stakeholders: upstream and downstream?

As the strategy unravels into an eventual new mode of work in each division, moments of reflection from employees who are witnessing the change are key to understanding if the new norm is living up to its intention. If these are not captured, analysed and acted upon in good time, there is a risk of flaws being introduced leading to change friction, and eventually reticence back into old ways as staff, compounding the change issues into systemic problems.

There is also the scenario where change went ahead as planned in one division, but the output produced is either in a different format, are unprepared for the improved rate or requiring more manipulations for division(s) acting downstream, in which case your feedback loops would need a larger scope to capture both intra- and inter-divisional change dynamics and success factors to sustain the improved state via refinements as well as gauging what issues have been encountered or likely to be encountered by clients or other divisions depending on this work.

What responsive change process can be instilled?

It can be hard to envisage what possibilities and risks lay ahead of each initiative before trying it out. Managers can pick a process for dual dry-run; that is taking a routine work through both the new process and the existing one to compare. For tasks with straightforward logical flow from expected inputs to outputs the dual dry-run mode can be adequate albeit with quality backstops in place in the initial revamping period.

Turning to the more nuanced or conditional work modes where inputs can vary or require manual interpretation, there is signicant variability and hence more consideraton has to be allotted to where the benefits gained and risks introduced by the new process. This would include scorecards on the process itself: was it easy to induct employees to adapt, how likely is the output going to be qualified as complete and of satisfactory standard. Would you need support documentation or technical expertise to guide your staff through the new mode; its features and limitations.

Putting that perspective back into the management where new trends emerge helps prepare for conditioning the support as well as anticipate the effect on any interlinking operations across the organisation, along with attention to rising new strengths and weaknesses that are taken into account for impact.

Conclusion

Whenever management gets a plan into action in the workforce, the prevailing status quo is held on to, covertly, by staff who do feel anxious about the transition into the unknown, or where there is confusion about where workers stand: as valued individuals, as esteemed belonging partners with status in teams and as expert workers whose output and work effort is going to increase in ways they do not necessarily yet comprehend. The success of managers hinges on tracking the real picture on the ground before and during change, to gauge what every stakeholder reports back as they go into the transformation and be mindful of work and cultural collaterals as the process is rolled gradually to harness opportunities for growth to reinforce the good equally as effective as mitigating risks as they emerge when encountering the adverse.

About the author

Hisham Ibrahim is a Change Management specialist, management consultant and business coach based in Sydney, Australia. His experience spans over 17 years in electrical engineering, project management and management consulting.

email: info@ibera.com.au